Daniele da Volterra, David and Goliath, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

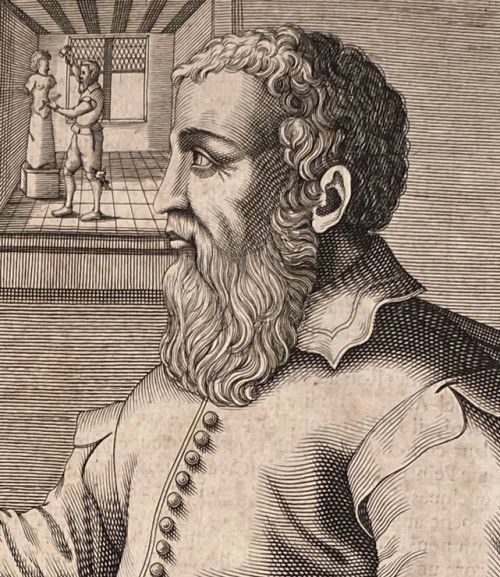

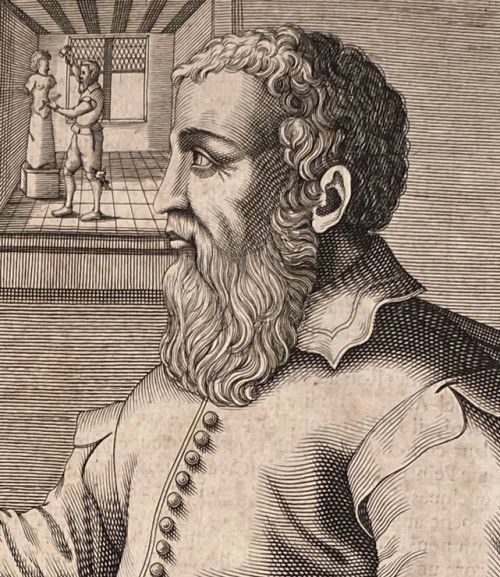

Portrait of Daniele da Volterra, pic.Wikipedia

Daniele da Volterra, The Descent from the Cross, Chapel Bonfil, Church of Santa Trinità dei Monti

Daniele da Volterra, Assumption of Mary, Chapel della Rovere, Church of Santa Trinità dei Monti

Daniele da Volterra, Assumption of Mary, fragment, Chapel della Rovere, Church of Santa Trinità dei Monti

Daniele da Volterra, Presentation of Mary in the Temple, Chapel della Rovere, Church of Santa Trinità dei Monti

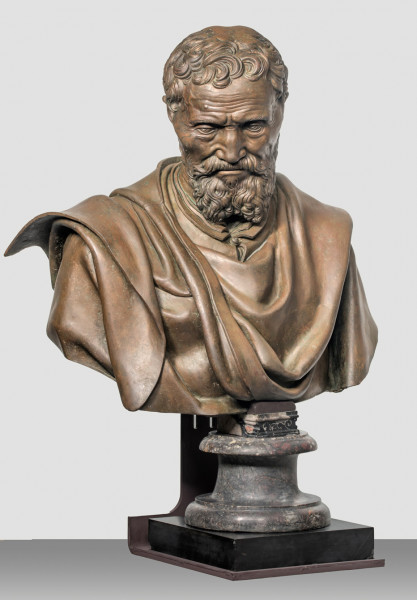

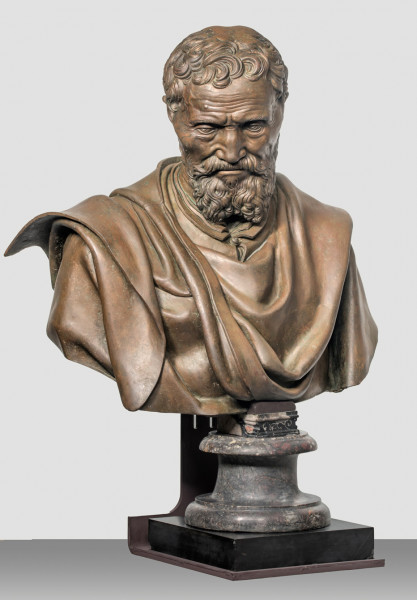

Michelangelo's bust, Daniele da Volterra, Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze, Firenze

Ricci chapel, church of San Pietro in Montorio

Daniele da Volterra, St. Peter, Ricci chapel, church of San Pietro in Montorio

Marcello Venusti, St. Blaise and St. Catherine of Alexandria before the intervention of Daniele da Volterra, The Last Judgment, Micheangelo, Apostolic Palace, pic. Wikipedia

The Last Judgment, Michelangelo, St. Blaise and St. Catherine of Alexandria after the intervention of Daniele da Volterry, Apostolic Palace, pic. Wikipedia

This artist was remembered for work, which brought him neither fame nor acclaim. However, as a painter and a sculptor he left behind several outstanding works, which for two centuries attracted art enthusiasts from all over Europe. Today we see him only as an imitator of Michelangelo, but also as his violator. And although this opinion is slowly changing, we still cannot fully appreciate his works. Why? Simply because most of it was destroyed and irrecoverably lost.

This artist was remembered for work, which brought him neither fame nor acclaim. However, as a painter and a sculptor he left behind several outstanding works, which for two centuries attracted art enthusiasts from all over Europe. Today we see him only as an imitator of Michelangelo, but also as his violator. And although this opinion is slowly changing, we still cannot fully appreciate his works. Why? Simply because most of it was destroyed and irrecoverably lost.

He was born in the Tuscan town of Volterra (hence his nickname). His first lessons were most likely under the watchful gaze of two skilled students of Raphael – Sodoma and Baldassare Peruzzi. Along with the latter, at the beginning of the thirties of the XVI century, he went to Rome in order to take part In the decorations of the Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne. After Peruzzi's death, he stayed in the city on the Tiber, which provided numerous opportunities to the young artist. He enrolled in the Academy of St. Luke and began establishing contacts with the artists who were active within the academy including Perino del Vega (also a student of Raphael). A decisive moment in his artistic life was encountering the famous, and greatest artist of all time – “the divine” Michelangelo. A friendship developed between them, while the lacking in self-confidence, melancholic, slow, and still searching for his path Daniele found in the similarly to himself secretive master true support. Michelangelo provided him with drawings, gave advice, but most all supplied him with commissions. It is probably thanks to him that Pope Paul III, entrusted the artist from Volterra with the post of superintendent who was to oversee the painting works in the Apostolic Palace, including the decorations of the famous Sala Regia.

However, a breakthrough in da Volterra’s career came when he obtained a commission in the Church of Santa Trinità dei Monti. The rich stuccos which he completed, but above all the magnificent frescoes amazed everyone.

In the fifties of the sixteenth century, perhaps under the influence and impression of Michelangelo, da Volterra more and more often reached for the chisel, proving his skills. Unfortunately, his sculptures along with the aforementioned frescoes were also, to a large extent destroyed.

In 1564, da Volterra along with Tommaso Cavalieri kept vigil at the bedside of the dying Michelangelo. A very moving letter to Giorgio Vasari (his chronicler) has been preserved, one which describes the grief caused by the death of his "master and father", which left him without – as he writes – "the sweetness of life and advice." At the behest of Michelangelo's family, he created a posthumous mask as well as a bust in bronze. Saddened by the death of his patron and friend he settled in his humble Roman home not far from Trajan's forum.

The Council of Trent, whose talks (after nearly 20 years) had come to an end in 1563, set out new trends not only in the teachings of the Church but in art as well. From now on it had to be created in the spirit of the Counterreformation. Any kind of indecency, for example, nude figures, had to disappear from any and all sacral interiors. Religious works were to inspire mortification, repentance, and prayer. The papacy, at that moment, faced a dilemma: how should these guidelines comply with works already found within the very heart of the Church itself, in a place which was the most famous and representative among all the works of art – in the Sistine Chapel, with the Last Judgement completed by Michelangelo. We must remind ourselves that the criticism of this work, coming from among others Pietro Aretino, started as soon as it was unveiled in 1541. However, none of the following popes reacted to it, not even the severe Paul IV. It was not until the death of Michelangelo, that the subsequent pope, Pius IV, in face of the ongoing discussions and agreements of the Council, ordered the indecent nudity of the figures to be covered up. This work was to be undertaken by none other than the still grieving over the death of his master Daniele da Volterra. From that moment he was scorned by his peers and acquired the humiliating nickname of “Braghettone” (The Breeches Maker). Probably, in spite of himself, the painter began working, removing the nude penises and breasts painted by Michelangelo and putting on new frescoes with fancy breeches, loincloths, and sashes. At the order of the pope, he also removed one of the scenes which was especially insulting to the eyes of his contemporaries. This was St. Blaise leaning towards St. Catherine of Alexandria who was bowing in front of him, and who seemingly surprised turned her head towards the saint who was “hassling” her. Catherine was dressed up in a green robe, while Blaise changed the direction of his gaze: from now on he looked in the opposite direction – towards Christ.

Defenders of da Volterra underlined his skill and restraint in covering up the intimate parts of the protagonists of the painting, which if he had refused would have been altered by another artist anyway. They claimed that in this way he saved the masterpiece which could have been completely destroyed. What would have Michelangelo said? We can only assume that he would not agree to such an intervention believing as he did that beautiful nude bodies are in themselves the emanation of God, but…could we really be sure?

Works on the alterations of the Last Judgement were halted at the moment of the death of Pius IV (December 1565) – it was necessary to take down the scaffolding in the chapel which was being prepared for another conclave. Daniele da Volterra did not return to them – he died a few months later.

The conservation of Michelangelo’s frescoes which was completed in the nineties of the XX century, and which had lasted nearly two decades, led to the removal of numerous additions (with tempera), completed in the XVI and XVII centuries by the continuators of da Volterra’s work. However, the ones he completed were preserved. Thus, in a way, he became the co-creator of this magnificent painting.

Daniele da Volterra’s works in Rome:

- Frescoes in the Orsini Chapel (unpreserved, apart from The Descent from the Cross), 1546; frescoes in the della Rovere Chapel (The Assumption of The Virgin, The Presentation of Christ in the Temple), 1550, Church of Santa Trinità dei Monti

- Decorations in the Palazzo Farnese (Stanza del Cardinale), 1549

- Stuccos and frescoes in the Apostolic Palace, Sala Regia

- David and Goliath, 1550, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

- Saint John the Baptist, Pinacoteca Capitolina (attributed)

- Holy Family with John the Baptist, approx.. 1560, Galleria Doria Pamphilj

- Frescoes in the del Crocifisso Chapel according to the cartons of Perino del Vega, Church of San Marcello

- Statue of Archangel Michael in the portal of the Sant’Angelo Castle, 1556 (unpreserved)